If “I am my ancestors’ wildest dream” was a person, Young Paris would be the embodiment of the musical, sociopolitical and aesthetic visions that the people of the Congo had of themselves lifetimes ago. Milandou Badila’s rise within the music industry as “Young Paris” as well as his persona as an aspiring fashion icon do not simply reflect his personal ambitions, they are also a mirror image of the story of how Congolese music came to become a global force to be reckoned with.

There’s a way in which African people manage, create and adapt in the midst of perils. As World War II raged on, the musical landscape of the Democratic Republic of Congo, then called Zaire, was infiltrated by Latin music from Cuba. When local artists began to adopt aspects of these musical styles and fused them with local folk music, it gave birth to what was colloquially called “Rumba”. Many of the genres that came throughout the decades such as Kwassa-Kwassa, Ndombolo and Soukous were originally dance moves that became musical movements in their own right. As the music evolved it then gave Congolese artists a channel into Europe.

By a similar sentiment, Young Paris’ father used an imported form of dance – ballet and founded the Congolese National Ballet. This career opened up the world for the Badila family and they moved to Paris, which is where young Malindou was born. When he was eight years old, the family moved again, this time to New York where he spent his formative years. As a family, they performed Congolese dance and drumming at schools and cultural events. This meant that his upbringing was steeped in his cultural history regardless of where he lived. In the midst of all that, one thing was certain for him; “I always knew from a young age that I would be a superstar. I always knew that I was here to bring creativity and growing up I just had to figure out what that was. Whether it was getting into music or fashion, I always knew that it would be something”.

The cultural shock that came with the move to America could have led to an identity crisis of some sort, “Here we are talking about black Americans”, he explains, “who are associated with their own history. Growing up here we were called African booty scratchers”, he laughs. “For me as a kid that was tough, you know? You don’t understand why people who look like you speak sideways to you, almost like you’re the enemy”.

He credits his parents for helping him to stay grounded in his identity because he saw other black youth who struggled with fitting in a society that was unwelcoming of those who looked like him. “It all depends on your outlook, how your parents raised you. My parents were very positive, very strong about our cultural lineage so I was taught to be very proud to be Congolese when I was growing up, even though other people would sh*t on us for being African. With time, guidance and the right type of parenting, a lot of people that I know, didn’t have their parents explaining to them these cultural differences so they would just be like depressed as kids at school, believing that they didn’t have much value.”

It was around the time when 50 Cent dropped ‘Get Rich or Die Trying’ when the teen Malindou began to form his own musical identity. “That was a big moment in the culture”, he remembers, “standing in cyphers and by what was happening around you”. Yet the layers of his own unique background instilled a different sensibility in terms of his musical sense of expression. On the one hand, Europe had exposed him to a wide spectrum of EDM influences and the chest-thumping bases had a deep impact. On the other, he grew on that African sound that had rhythms that hit right in the bones.

That’s when he dropped his first album ‘Rap | Electronic’ in 2014. He says about the album, “I was trying to figure out my sound. I was trying to figure out how to bring my vibe into the world. I was playing with electronic music, I was playing with African music and I was playing with hip-hop. At that point, I wasn’t really influenced by a lot of music or messaging that was happening in pop culture. I was just like ‘I’ve listened to a lot of hip hop growing up and African music in my house’ so I started mixing these two styles together.”

When he dropped ‘African Vogue’ in 2016 that Young Paris came into his own. “It was African Vogue that got me signed”. By that, he doesn’t mean being signed by just any run of the mill label. In that year he was signed to RocNation. “At that time no one was even aware of contemporary African music and their message. D’Banj and Don Jazzy and a few of these guys were just starting to kick off.” The release of African Vogue did more than put his rap prowess on blast, it also cemented an aspect of identity that sets him apart: his fashion persona.

When the Congolese people were colonized by the French and Belgians, it was common for those who worked for the colonizers to be paid with secondhand clothes instead of cash. The Congolese took these and did with the clothes what South Africans did with the All-Stars, the Florsheim shoes and the Gusheshe, they created an entire self-assured, empowering identity out of them. Thus, the Congolese Sapeurs were born.

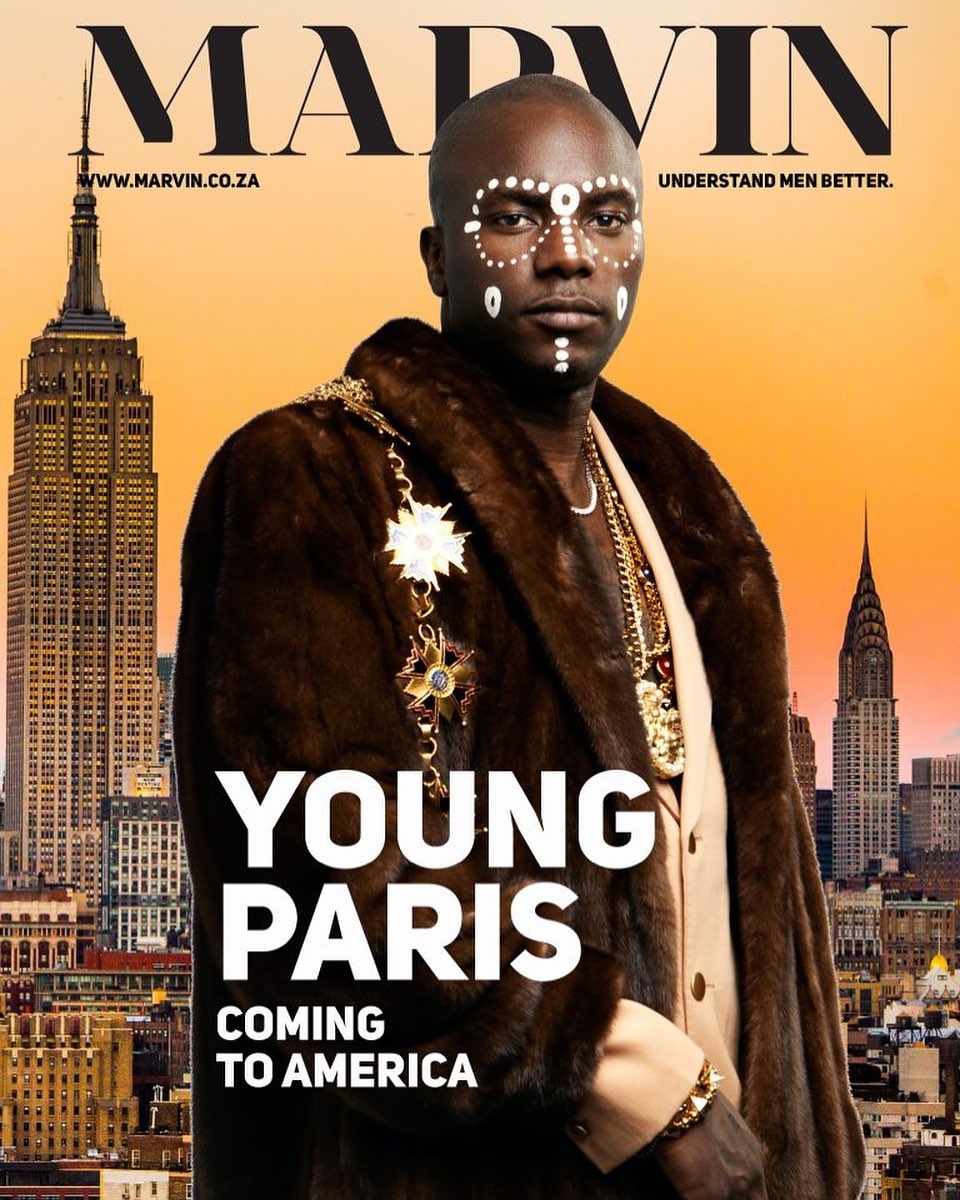

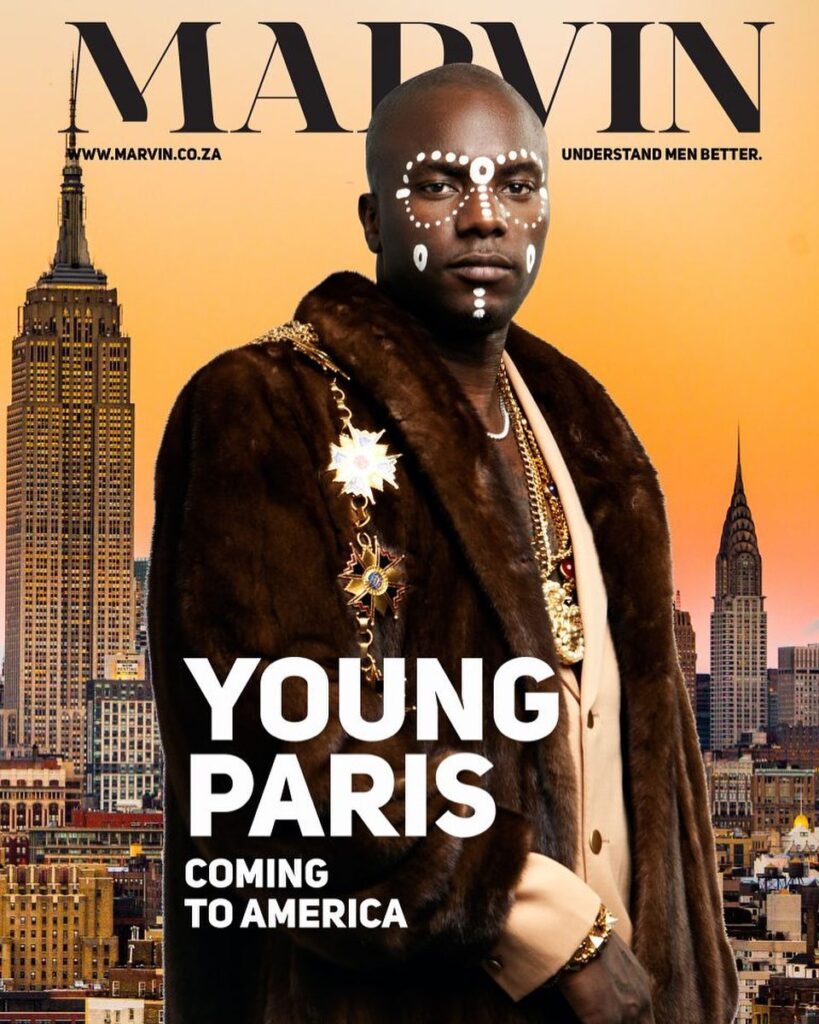

Commonly called “African Dandies”, Sapeurs are individuals who have taken fashion as a weapon of self-expression. They are impeccably dressed men and women who hang out in social gatherings draped in flamboyant, almost theatrical outfits that scream for attention yet retain a sophistication that scoffs at the squalor in which its disciples come from. The clothes are a mix of classical European fashion, accented with bold African colours and patterns all wrapped in cuts that don’t bother with body types. One look at some of Young Paris’ outfits and becomes clear that he’s a Sapeur right to the bone. His fashion appeal has also seen him gracing the pages of prestigious publications such as Vogue and Harpers Bazaar.

Just like the Sapeur OG’s from DRC, Young Paris’ fashion aesthetic is not an accessory to his music, it is a sociopolitical statement about his whole being. The roots of Sapeurism dig deep into the fight against systematic brutality, it is about owning one’s identity and using the instruments of oppression to weaving a thread of self-expression through it to create the tapestry of freedom, in form and in function. The irony of fashion as a weapon is not lost on him either. “With African Vogue, I wanted to use these paradoxes (music and fashion) and say African are Vogue and when you think about these high fashion statements and where they come, the original source for a lot of these images and ideas in Africa”.

On his face Young Paris wears distinctive maquillage (white paint patterns) that not only set him apart but carry a deep personal meaning. “When my father died in 2012 not only was wearing the face paint a way of coping with his death, but also a way of solidifying how I want to translate my image into the world and into the music. At that point, I was like “listen, man, this is the man who raised me and who made me proud to be African and what better way to keep his identity strong than to keep the marks that he gave me. So right away I knew that I wanted it to be a very strong part of my image”.

Despite signing under the American label, the social commentary embedded on much of Congolese art finds a comfortable home in Young Paris’ work. The cover of his latest album juxtaposes a luxurious scene that looks like a high fashion spread with the album’s title: ‘Blood Diamond’. He seems to thrive within the paradoxes and explains the idea behind the album:

“I wanted to challenge the conversation around diamonds because us being Africans and being the home that sources a lot of these raw materials, I wanted to challenge that subject matter. People forget that the diamond isn’t the issue nor any kind of raw materials… It’s more about what the humans have done and how they create these catastrophic industries around minerals. So ‘Blood Diamond’ was my way of saying “we’re these African kids who come from these areas of conflict and make it to these places like Europe and America similar to a diamond”

Marvin App™ is also available on the iPhone/iPad and all Android tablets. The widescreen app gives you a larger than life and greater experience of this cutting edge design.

Writer: Vus Ngxande Photographer: Luke Bennett Stylist: Iman Granger Copy Editor: Palesa Motau Creative Director: George Gladwin Matsheke Partner: Merchantry World Wide