It’s a hot summer night in Umlazi. Max’s lifestyle one of the premier music venues in the area is packed to the rafters. Riky Rick is at the tail end of his set. The place is a mosh pit as young hypebeasts in five panel caps and girls in flower crowns and high waste jeans become slaves to the rhythm. Riky has been on stage for almost forty minutes now, letting loose some of his signature tunes from Boss Zonke and Nafukwa to Summer time and Amantombazane. Everyone in the crowd has their hands in the air as if reaching out to a higher power. The stage is small, no more than 4 x 4 meters. There is security around but they wouldn’t be able to do anything if the crowd decided to invade. The only thing keeping the people at bay is how Riky occupies the stage, from left to right he twists and turns, adjudicating the dance electric, spitting familiar bars and allowing the audience to recite lines along with him. At one point he just shuts up, the beat falls silent and the crowd does the entire hook and second verse of Boss Zonke in unison.

It’s a ceremonial moment, he is home. Riky was born in Umlazi not far from here. I first saw him at a Ben Sherman show some years ago when he first joined Motif records. He was not what I expected. He didn’t have the cadence and distinct flows of a Tumi nor the playful bars of a Reason. He could make music but that’s not saying much, and didn’t seem to fit the Motif mould. If then had you told me that less than three years later I’d be watching him manipulate the crowd with such ease I would have laughed you off. I am one of those who didn’t believe.

It’s difficult to speak about Riky and his music because he occupies a weird space where he does a lot of things well but those things are difficult to quantify. His greatest instrument as a musician is not his ability as a rapper (although he has been spitting a lot of fire lately) or his ability to put words together. He is a good storyteller but then again many South African rappers are, Riky Rick’s best gift is his ear. He has a musical sensitivity that transcends the boundaries of hip hop. Take his first big solo hit Nafukwa for instance, the song with trap kicks, layers of strings and a chant that feels ancient is one of the most important songs ever made in South African hip-hop. When it was released in 2014 it sounded of the moment but in an era where the expiry date on music is mere weeks, it has held up incredibly well, is almost instantly recognizable and my feeling is that it will stay that way for some time to come. Sondela is another example of this, nothing about that beat or the hook says rap, but through a smart flow and changes of tempo he managed to make an incredibly tender record that does not get the credit it deserves.

After the show in Umlazi a music photographer friend of mine and I head out to Johnny’s rotis. A small place in inner Durban whose menu is designed around the expectation that club goers in the witching hour need something comforting to munch on. We order two chip and cheese rotis and as we sit in the front seat of the car chomping away he says, “Riky has grown on me you know.” I have a feeling that, when asked a lot of people feel the same.

King Kotini claims his crown

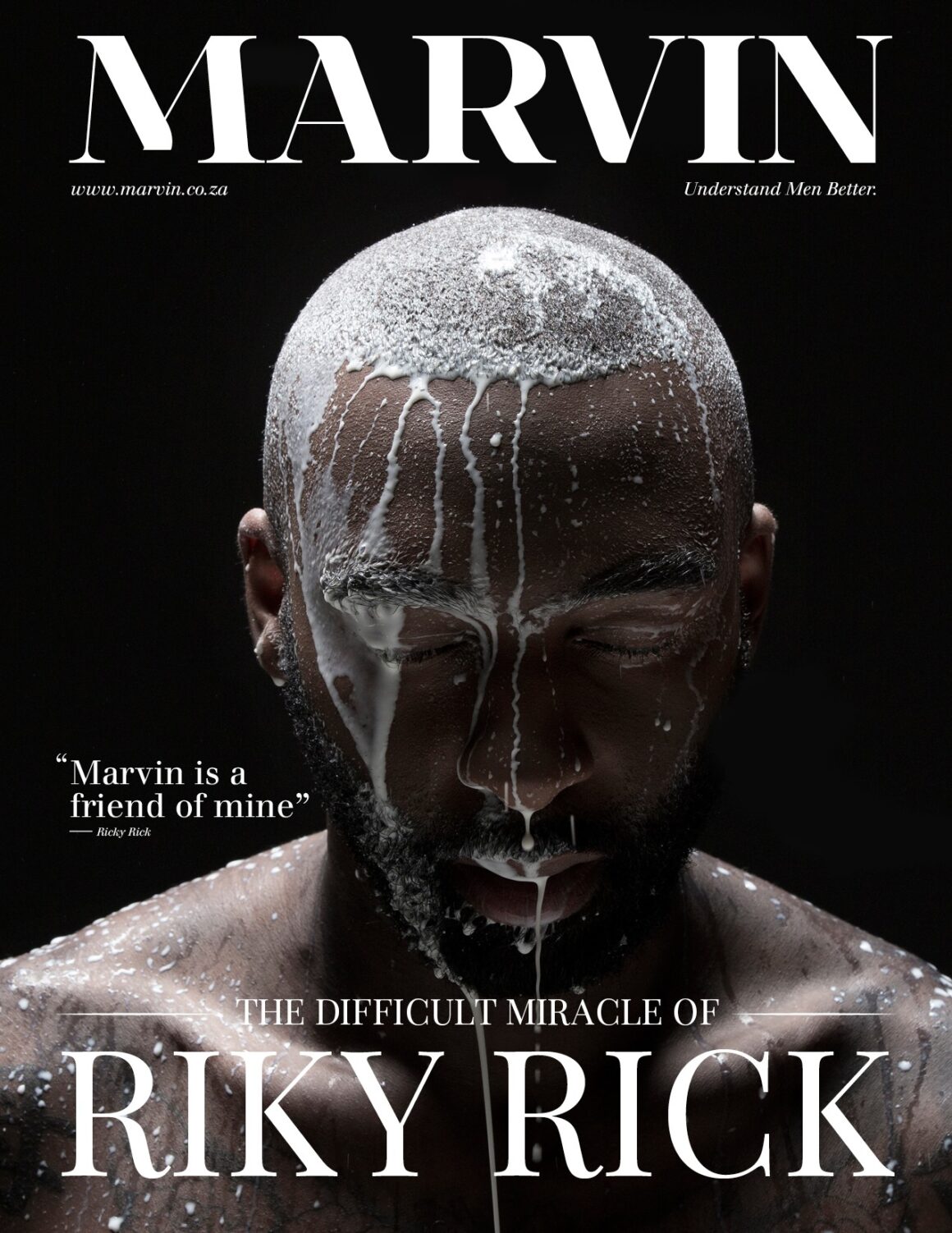

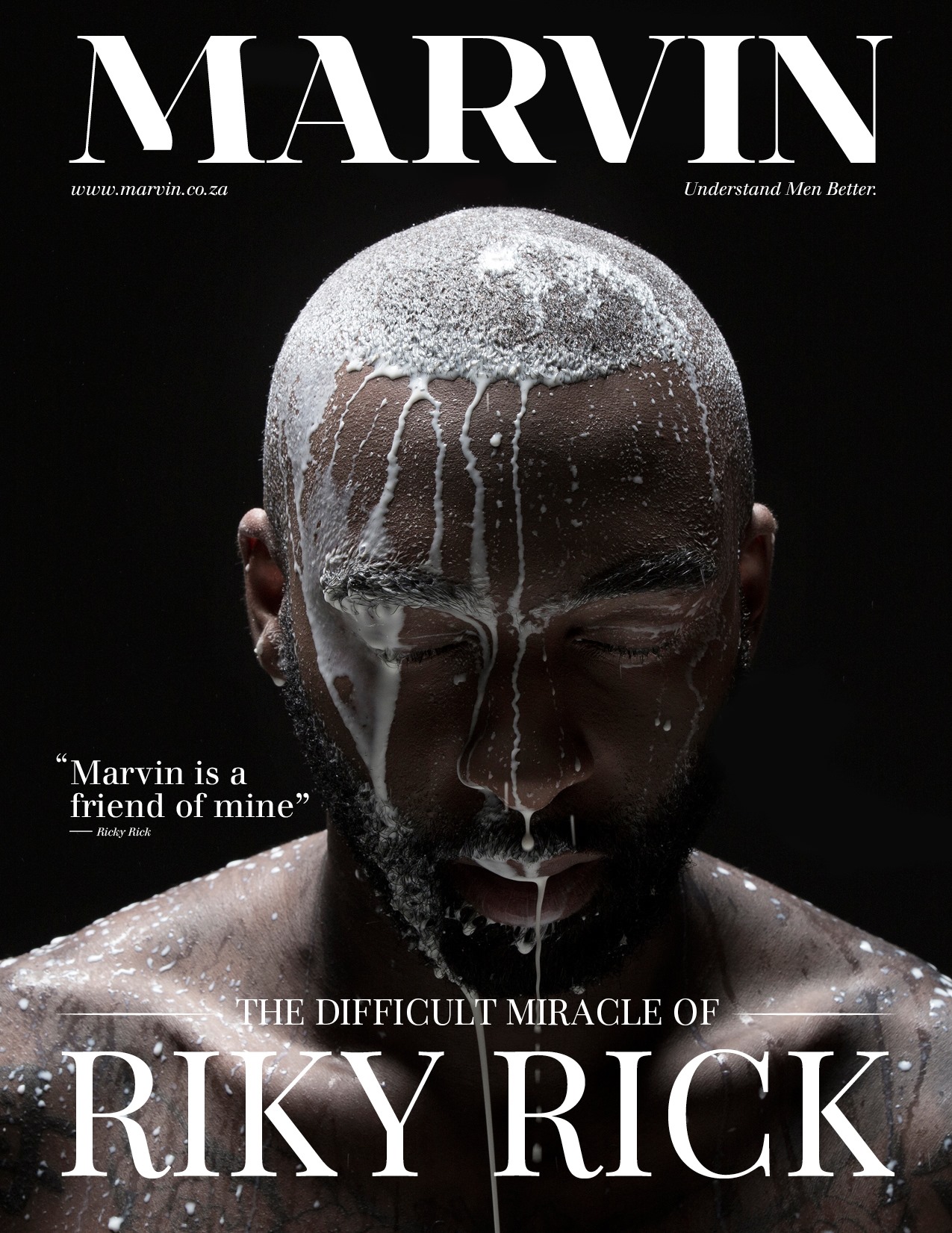

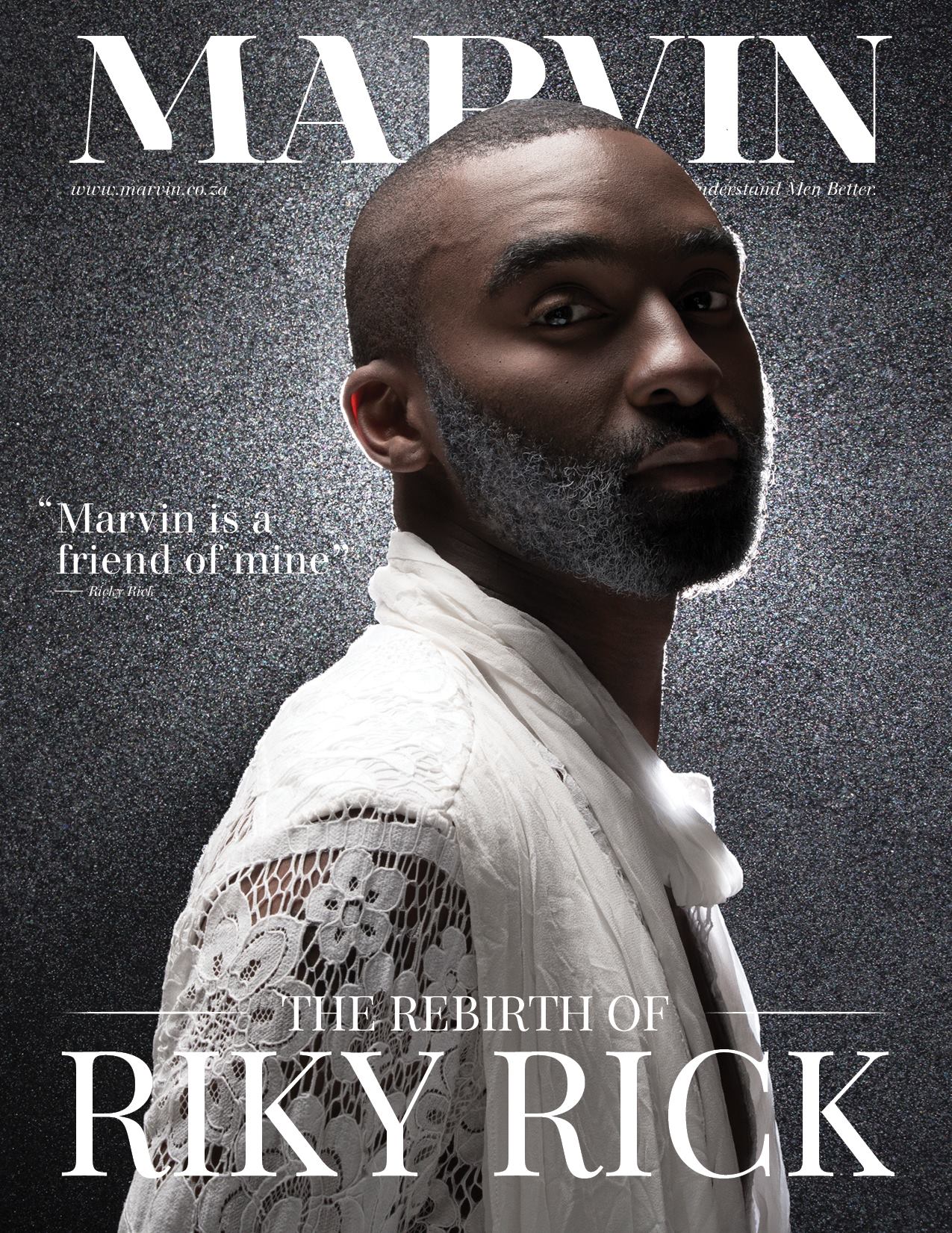

King kotini understands that in entertainment, perception is the only commodity that counts. He is also the most photogenic musician of his generation. His tattoos adorn his back and chest like soldiers occupying foreign land, his shinny beard, clean and low cut and the bald head, remind me of Joe Budden, minus the dimples that often make Budden hard to take seriously when he is talking real stuff. His persona and visual aesthetic is one that is simultaneously obsessed with beauty yet keenly aware of how benign it can be.

But the kind of beauty Riky practices has no mereness to it. He taps into the historically loaded culture of black dandyism. Through carefully curated fashion choices and a constant construction of his photographed images he is able to load himself with the kind of dignity historically denied to black people in general. On the cover art of Family values Riky can be seen in blue jeans, cradling his son in an almost madonna and child like manner. He is topless and looks directly at the camera both taunting and teasing it. In a hip hop environment where masculinity is the driving force and daily we are bombarded with images of the traumas endured by black children because of absent paternal figures, The family values cover is a moment of both vulnerability and disruption. There are also some parallels here with the work of conceptual artist Mohau Modisakeng in the way history is remixed, manipulated and reckoned with, the emphasis always placed on exploding into your blackness.

Riky Rick is actually a very small guy, his shoulders are not broad and he is not particularly tall but he has a presence about him that demands the attention of the room.

Before that show in Umlazi with him wearing a black and white bomber jacket, baggy jeans and a cap, Riky was not his usual overpowering fashion killa self. He would have been easy to miss. With an entourage of just two guys he makes his way into the VIP section to a table in the middle of the room and sits quietly. Drinks start to flow around him, all the while he is on his phone occasionally flipping the screen to show something to one of his boys, they laugh and he goes back to scrolling.

When I first saw the billboards for his previous campaign with an alcohol brand I thought a lot about this moment. That in just a matter of years a young boy from Umlazi who had spent his whole life battling drug and alcohol addiction was now selling vodka. To some this endorsement didn’t make sense, but when you consider that the desire for control is a recurring trope in Riky’s story, the picture starts to fall into focus. Here he was taking the thing that almost ruined him, making money of it and changing that fear into his freedom. By contrast his new campaign with Vaseline is one driven by an organic connection. His marriage with a legacy brand like Vaseline is the first hint that Riky is playing a long innings. He has shifted his focus from the transient connections that are often the partnerships between artists and brands into something more substantial. He is a key ingredient in helping thrust a brand that is inextricably South African into the 21st century.

In the weeks leading up to announcing the partnership, Riky started rolling out his new mantra, start strong, stay shinning. Later it would be revealed that it is connected to his campaign with Vaseline. But those words seem to have already resonated with his fans beyond the borders of just an artist endorsing a product. They speak to his current situation and have meaning because they are about his constant thirst for persona reinvention. Something which has earned him legions of supports and the respect of his peers.

As he sits, eyes glued to the screen a line starts to form and he takes pictures with some admiring fans. At our table were a couple of guys from Mozambique and Zimbabwe who we were entertaining for the weekend, they rush through to snap some selfies with King kotini. He smiles throws a deuce and the flashes illuminate his face.

You can see his relief when the whole thing is done. Not because he doesn’t appreciate the love. But because despite his onstage persona, Riky is very shy. He hardly makes eye contact and in person he doesn’t say much. You get the feeling that the real estate that often comes with fame and being King Kotini is tedious for him. He’d rather be at home playing video games with his son Malick.

In an age where the word artist and brand are often interchangeable, creative autonomy and economic imperatives are muddy waters. People can never say what they mean because they no longer speak just for themselves. They are the mouth pieces of corporate culture and are as restless as capitalism itself. And here is what makes Riky unique, he says what he means and often it is said though his medium of choice, music.

When he left Motif records he addressed his departure by saying that he paid Tumi his money and thought they were square. He expressed his fear of failure by pointing out that he does not want to end up like veteran rappers Ma-E, Jabba and the late Flabba. This direct talk attitude has earned him many admirers and paradoxically makes him indispensable to brands

In 1962 author and essayist James Baldwin delivered a talk at New York community church. The session was recorded and the audio although not complete can be easily found on the internet. This is one of the more overlooked Baldwin lectures but also one of the most insightful. Not only about him personally but his frustrations with the world he occupied as an artist in search of integrity. In it he points out, “The crime of which you discover slowly you are guilty is not so much that you are aware, which is bad enough, but that other people see that you are and cannot bear to watch it, because it testifies to the fact that they are not. You’re bearing witness helplessly to something which everybody knows and nobody wants to face.

So on that chilly Durban night, dressed in a pink jacket and silver pants as he took to the Metro FM awards stage to denounce the industry he had worked so hard to be a part, there was a moment of pause. He looked at the award his eyes glazed over as if only then understanding that in this industry merit was an enemy and that he would always be a perpetual outsider. He took revenge for the dreamers.

He reminded a South African music industry that has grown comfortable with repetition that he is part of a generation that has had to come for everything. In an emotional speech that has far too often been dismissed as a rant he terrified executives and terrorized sponsors who would have expected a much more civilized affair before being taken off air.

Being intimately aware, of how these productions work, in my head all I could hear was a panicked producer screaming shut it down. In a generation wuss moment where college students are insisting on trigger warnings before being read passages of Shakespeare or Toni Morrison, this moment caught people completely off guard. Vulnerable to the truth.

The speech was important in all the obvious ways. Here was an artist putting himself on the line to speak about the horrors of a music business at all levels at war with itself, here was a man making a direct connection between himself and the dozens of other kids like him who have talent but feel they will never be heard because the gatekeepers are not willing to listen.

But it was also important in more subtle ways. Years ago we used to have what were called conscious rappers, they were the custodians of social justice messages whilst everyone else made party songs. The fact that it was Riky Rick, a mainstream commercially successful artist at the peak of his powers who was speaking out against the establishment made the moment powerful in ways that will undoubtedly reverberate into the future.

One of the things that has happened since he announced he was leaving Mabala Noise, has been the flood of support shown by his fans. It is an indicator of the good will he has built up over the years. They have asking him to be strong and stay shinning. People are worried about who he will become because the thing he is best known for has come to an end.

But Riky Rick grew up in Umlazi during the height of kwaito and instead decided to rap, he fought drug addiction and worked his way from an emotional wasteland into the consciousness of South African music. When he and Motif went their separate ways, he made a platinum selling album which he was selling out of the back of his car at shows. He has been here before. Leaving Mabala noise is just the latest shift in a jigsaw career that has been defined by constant change and one man’s ability to adapt to it. Leaving Mabala Noise is not the end of Riky Rick, it is his latest chance at a second act.

Writer: Sihle Mthembu Photographer: Judd van Rensburg Stylist: Mpumi Sinxoto Make Up: Tsholo Ramashala Creative Director: George Gladwin Matsheke