“I took it upon myself to not just sit at home and be a leech. So, I took all my artwork as well as my portfolio bag and just went into town. I didn’t know what I was going to do in town or who I was going to meet, I went to town and I sat at Gandhi Square and I just started crying. I didn’t know what was going to happen. I couldn’t afford an education – I didn’t qualify. I couldn’t get a job. So, I just cried. I just sat at a bus stop and just cried, and I cried it all out. Then I got up and decided to go back home.”

This was not how this article was supposed to start. It was supposed to start with the opening lines of Charles Dickens’s “A Tale of Two Cities”. The idea was to set the scene of a young man born in the Democratic Republic of Congo and raised in the Republic of South Africa. A young black man who had to learn to balance two identities. Perhaps, on that point, a quote from W.E.B Du Bois’s “The Souls of Black Folk” would be fitting. Like the part in the book where he talks about “a peculiar sensation, this double-consciousness, this sense of always looking at one’s self through the eyes of others, of measuring one’s soul by the tape of a world that looks on in amused contempt and pity”.

It was this tendency of measuring our souls by the tape of the world that led to the young black man shedding defeated tears, alone at a bus stop clutching tightly at his work and his worth in a world that neither pitied him nor was it amused by his plight. The world simply did not acknowledge his existence.

It was a day after he had been forced to quit his studies in graphic design at a private college. He had wanted to study at WITS, but his English marks were two points short. He had studied French. The irony of not being allowed to further your studies because your people were colonized by the wrong country. The private college was expensive. Three months into the course he got a call from his father telling him that they could not afford the fees and he had to drop out.

It is the kind of betrayal that many black youths are too familiar with. “Society conditions”, he says “you to think that you need to get through school and get qualifications to be someone in life. And I am not saying education is bad if you can educate yourself, go and do that, but then I was just like, ‘ok cool, this is probably the end for me because if I can’t finish this degree what am I going to do? Especially as a man coming from an African family where you are supposed to be the head, the breadwinner”.

But as the firstborn in his family, resilience was the ink in his pen and art had been a way for him to “help tap into worlds and imaginations that I could not express verbally”. So, early on, he had to learn to be resourceful and self-reliant, qualities that became indispensable for one born in a time when technology was reshaping the world. In his formative years, MySpace was falling off, Mxit was still a thing and BBM was hype. He had matriculated in 2012, an era in which social media as we know it today, was slowly becoming the lifeblood that connected the world. He came from a traditional African family that only recognized doctors, lawyers, and teachers as the only path to a decent life, dignity, and heaven. “I knew I wanted to be in the creative space, I just didn’t know how.”

In high school, he had already started messing around with Photoshop, learning photo manipulation through odd projects where he transferred his artistic talent onto a digital format. He learned how to use the internet to teach himself how to use design programmes and it was through this process that he began to grasp the potential of online not just as a source of entertainment, but as a way of bettering oneself. “Back then, digital entrepreneurs and content creators were non-existent. We didn’t know that digital was going to be what it is today, and content was going to be what it is today. Social media was just there for us to connect with our friends, talking to ourselves mainly, no one cared how many likes they got or re-tweets. No one cared about that stuff. We didn’t even see it coming. Influencer were people we saw on tv or heard on the radio”. As he sat at that bus stop in Gandhi Square, gathering his strength to go back home, “this crazy guy dressed in a colourful outfit was walking across the road and shouted, ‘GRAPHIC DESIGNER!’ at me and in my head, I’m like “I’m actually not a graphic designer, I don’t have that qualification but I have the skill’. He’s this crazy Congolese guy, he calls me over and he’s like “what’s up?” This “crazy Congolese guy” turned out to be Papy Kaluw. He is a self-taught fashion designer and founder of the now-iconic fashion house Urban Zulu. His company was struggling with navigating social media and he needed someone to help with photography and graphic design. “I showed him my work, which was mostly paintings, right there at the bus stop. He loved it and told me to come in on Monday”.

That’s how his career began, with a mix of dogged determination, God-given talent, and a good dose of being at the right place at the right time. The work that he did was essentially a crash course in social media management and it was “a period of me learning about online business and things like analytics, reach, impressions and knowing the perfect time to post on Facebook”. His future business partner, Elliot Sithole, also came to work at the same came company and it was here where they began to craft a new kind of agency. They identified the gap in how African brands fell into the trap of playing to the tourist gaze and a gimmicky approach to selling the African narrative. In 2014 he and Elliot started Creative Mind Space, a multidisciplinary ideation agency. Perhaps one of the most innovative aspects of the company is that instead of it being just a two-man studio, as is the case with many young creatives, they have created a network of “problem-solving creative engineers”. “It’s about finding ways of collaborating with different creatives”, he says. “How we see creatives is not only as designers or an artist. A creative could be a chef, a writer. In five years, we built an agency where you could find any kind of creative”. It is through this business model that Creative Mind Space has been able to work with some prominent brands in the country from Cadbury, Castle Lite to SA Fashion.

There’s a habit that people who approach life by colouring outside the lines have, where they don’t know where the boundaries are and, as a result, see opportunities that most would shy away from.As Creative Mind Space grew and he got the hang of social media, he realized that he could turn himself into a brand as well. One of the ways he could do this was to partner with brands to “deliver unique, stylish & bespoke creative experiences for their businesses”. One of these was the Bespoke Man and Jameson collaboration at Bespoke Man, an upmarket barbershop, where a select group of gentlemen are invited for a grooming experience and progressive conversation over some glasses of Jameson Whiskey. When you look at his partnerships, whether it is with Tanqueray South African or Tread and Miller, one thing is abundantly clear, his understanding of personal style is a part of the fabric of language of his very being. His dress code strikes an immaculate balance between nostalgic echoes of Sunday best outfits, the brash accents of Congolese sapeurs and the globalist cadence of the Sartorialist held together by his firm voice as an African man who is comfortable in his skin.

However, developing his brand isn’t confined to IG-worthy imagery. He has been sharing his insights on brand building and online marketing for some time and he’s built up a significant base of followers who value what he shares. Over time, more and more people have wanted to engage him personally seeking advice. Balancing a personal brand with a 9-5: “my business started to become a challenge”. For him, Creative Mind Space comes first and the online became exhausting with people constantly asking the same questions. “I’ve had to productize myself. I started threading my content”. He collated the questions that were getting asked a lot about branding and marketing and then started creating threads where he answered the questions in detail. “And that eventually became my product because I realized that I can’t be answering 15 DMs of the same questions. So I chose to rather extend my value and my knowledge and package it on a platform that people can easily access without accessing me directly”. But learning to productize his value didn’t just start and end with his social media presence.

“There was this one time I was walking through Small Street, back from work, and I see this black hat, right? And this hat looked so cool. It had this very mysterious thing about it. This is like the kind of hat that you would wear like the guy chilling at the bar alone having a drink. And I grabbed it, I think it was like R30. I started wearing that hat all the time and people started saying things like, ‘you actually look good in a hat’. Then I started buying more hats. I was consistently wearing hats and it’s funny because there are many people before who were wearing hats, celebrities, and influencers, but I sort of became the face of hats within the creative industry. Then I got people asking me things like, ‘this is my head shape, what kind of hat should I wear?’ Or ‘how do you travel with your hats, how do you take care of your hats?’ Then I was like, hold on, wait a minute. There might be a market here”

That is how he came to launch his line of hats. It is in how he describes the hats that you get a glimpse into how he views not just himself, but the world around him. “Each hat has a story”, he explains. “The one hat that I have is called The Mystique. Dark green finished with burn marks, it’s a very mysterious guy who sits at the park writing down his thoughts in a journal. He is that guy who would walk into a pub and everyone would think that he’s probably an alcoholic or is on drugs because he’s so genius at what he does, and you could never wrap your finger around him”.

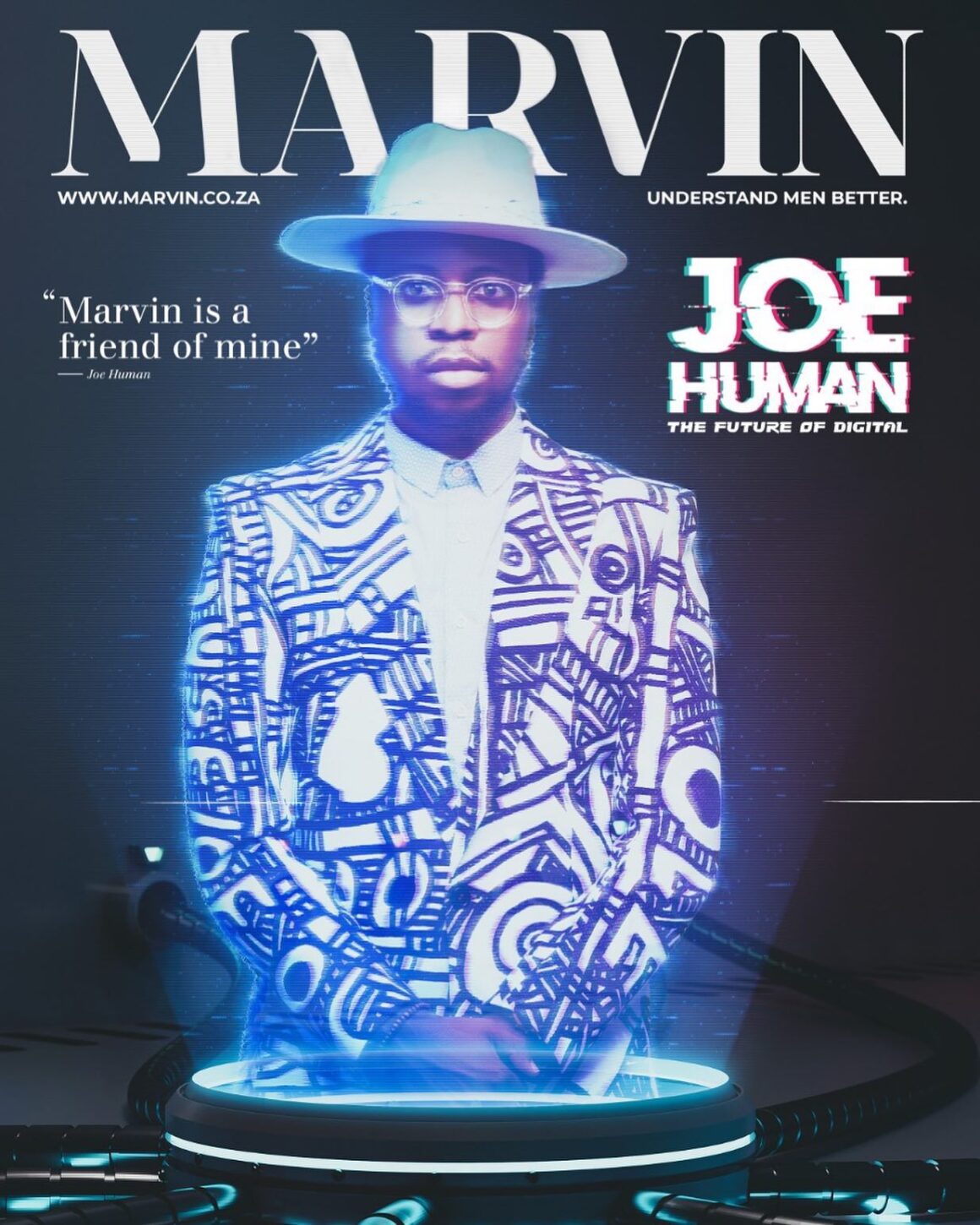

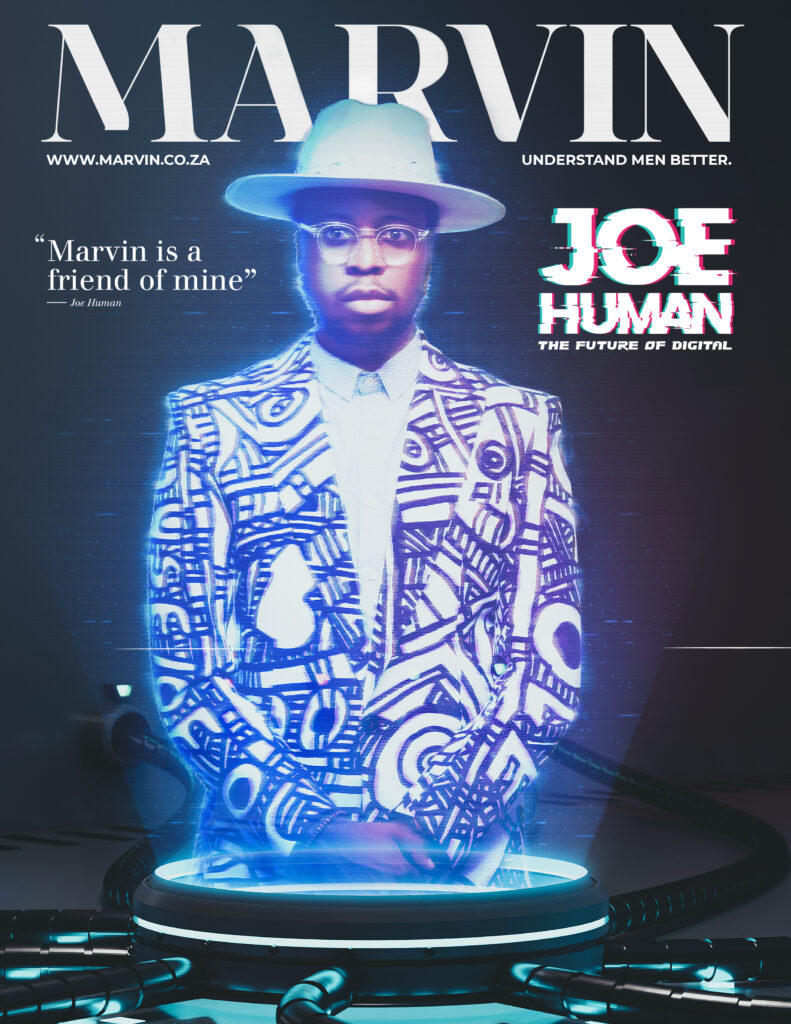

Our conversation turns to the rise of cancel culture especially in how it relates to black men. For someone who has built his brand based on the online presence, the realities of cancel culture put him in a precarious position where years of meticulous brand building can be destroyed with one tweet. He concedes that the trends have affected him especially in how he socializes. “I’m a home-bound influencer”, he chuckles. Nonetheless, he cannot do with social media not just as abusiness tool but because he values connecting with people. “Before race, sexual preferences, beliefs, and cultures, at the core of it all, we are all just human. That is why I added ‘Human’ to my name”. In many ways, he is one of the most amazing individuals that you could ever meet.

His name is Joe Human.

Writer: Vus Ngxande

Photographer: Jeff Rikhotso

Art Director: Jayson Grayford

Copy Editor: Palesa Motau

Creative Director: George Gladwin Matsheke

Jacket: House of Ole

Hat: Joe Human